Chapter 1 Deciding to experiment

Before embarking on the experimentation journey, you should ask the question ‘Do you have to run an experiment?’ As discussed in Module 1, experiments provide answers to very specific questions – they will likely not answer questions that are not causal in nature.

Designing an implementing an experiment can take time, motivation, skills, and often financial resources. It is not always immediately clear what combination of resources you will need for your experiment, given that they’re not the first thing considered when trying to answer a question.

Embarking on the experimentation journey will require significant cross-functional collaboration, stakeholder buy-in, and lots of preparatory work – but it all starts with having clear and thoughtful design for your research question, and then landing on an implementation plan before starting.

1.1 What is an experiment?

An experiment is a procedure designed to test a hypothesis as part of the scientific method.

Experimentation is often described as a method, approach, a test, a tool to generate evidence. All of these are true, but first and foremost experimentation is a problem-solving process. The starting point for any experiment should be the problem you are trying to solve.

The two key variables in any experiment are the independent (explanatory) and dependent (response) variables. The independent variable is controlled or changed to test its effects on the dependent variable. Three key types of experiments are controlled experiments, field experiments, and natural experiments.

Controlled Experiments: Lab experiments are controlled experiments, although you can perform a controlled experiment outside of a lab setting! In a controlled experiment, you compare an experimental group with a control group. Ideally, these two groups are identical except for one variable, the independent variable.

Field Experiments: A field experiment may be either a natural experiment or a controlled experiment. It takes place in a real-world setting, rather than under lab conditions. For example, an experiment involving an animal in its natural habitat would be a field experiment.

Natural Experiments: A natural experiment also is called a quasi-experiment. A natural experiment involves making a prediction or forming a hypothesis and then gathering data by observing a system. The variables are not controlled in a natural experiment.

To summarize: an experiment is simply the test of a hypothesis. A hypothesis, in turn, is a proposed relationship or explanation of phenomena.

1.2 Do we need to experiment?

To embark on an experimentation project, we really need to consider whether experimentation is needed in the first place. One way of determining this is to consider whether there is a very specific question that requires a specific answer? And, is the answer worthy to know? If we are after questions that are not causal in nature, then an experiment is likely not the best fit.

Making observations or trying something after making a prediction about what you expect will happen, is a type of experiment. For example, predicting/hypothesizing that your coffee will taste sweeter after the addition of sugar and then going ahead to testing that is an experiment.

The following examples, on the other hand, are not experiments:

- making a model dashboard

- making a poster

- changing many factors at once, so one can’t truly test the effect of the variables

- trying something, just to see what happens.

At this point in the experimentation cycle, there are more questions than answers and the more questions one asks, the more clarifying answers one will seek on whether an experiment is really needed.

What would experimentation look like in policy or practice? why would an experiment be worth investing in? What data or program performance tracking is already in place? What experimental tools and expertise are available and are they sufficient? What are the risks? What could be a risk management strategy?

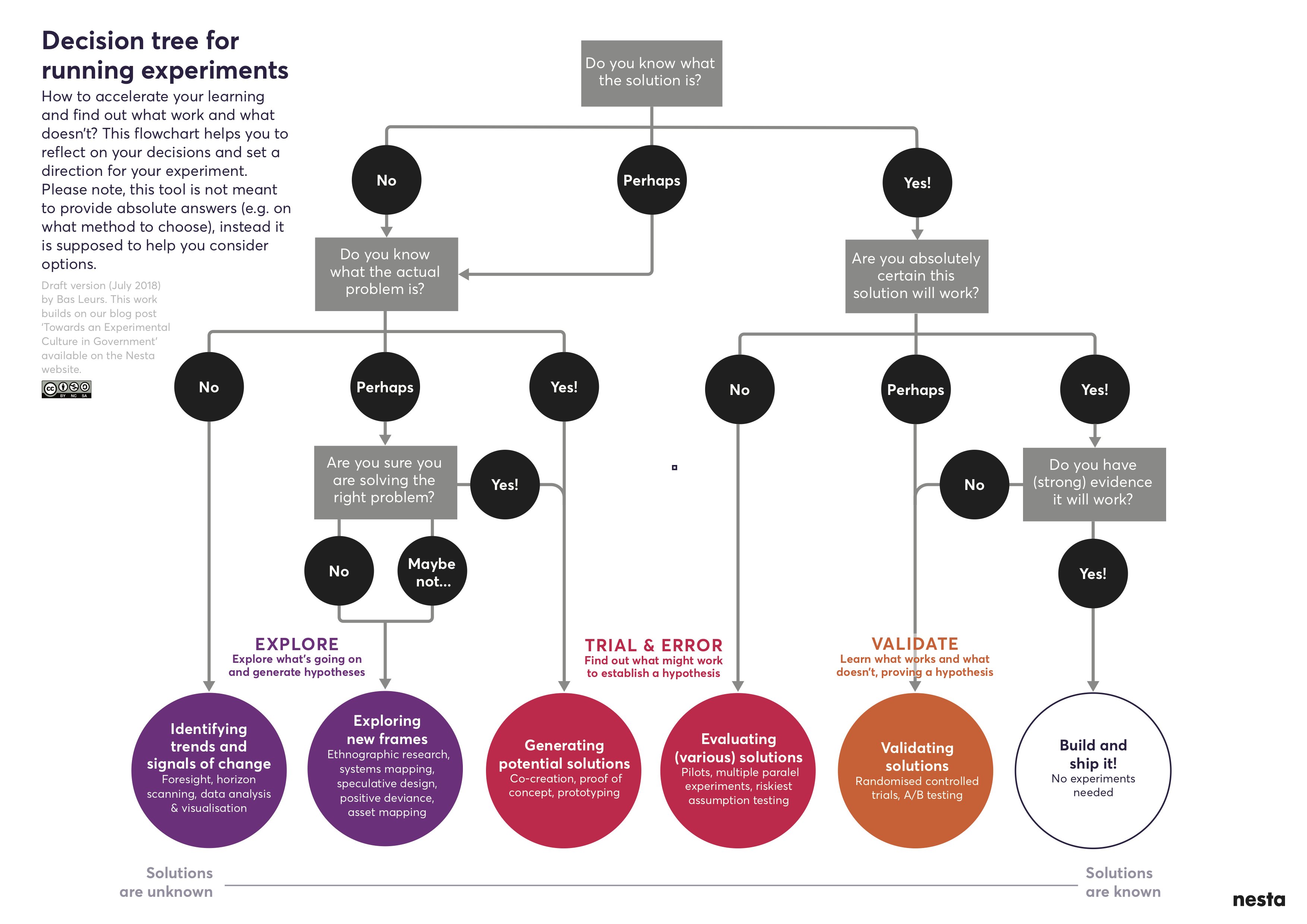

Decision tree

To help make whether an experiment is needed and set one’s direction, the following decision tree from Nesta is a great starting point for a project journey. In this journey, only the two red bubbles refer to an experiment. The rest are only explorations or validations. What makes the two red bubbles an experiment? What do they have in common? The two red bubbles focus on the trial and error to find out what works and what doesn’t, which is central to any experimental project.

1.3 The experimentation cycle

A problem well-stated is half-solved!

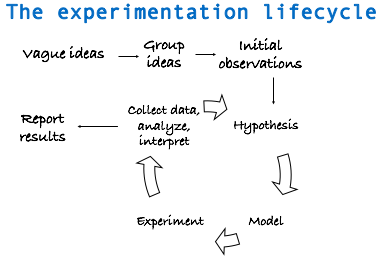

To help others understand the problem as we see it, one of the first things an experiment needs is well-framed question and clearly articulated goals. To help formulate the why as well as the what, the following experimentation lifecycle is helpful in that it encourages to reiteratively (1) brainstorm and form vague ideas, (2) group vague ideas, (3) make general observations, (4) hypothesize, (5) determine a model/method to test the hypotheses, (6) do the experiment to test hypothesis, (7) gather data, analyze, and interpret the results, and (8) learn and communicate learnings to stakeholders

This lifecycle presumes that we can:

- sketch out what information we need to collect (or already have) to get from a vague idea to the hypothesis stage for a planned project

- get invested in the problem before the solution nor in a particular result (any biases will work against us here)

- not get stuck in a fishing expedition (i.e. grouping ideas forever)

- understand the problem well enough to clearly articulate the goals, questions, and hypotheses before building metrics

- select metrics that will help answer the questions. This can include system parameters, workload parameters, behaviours, etc.

“If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” - Bernard Baruch - identify parameters that affect behaviour or observations and decide which parameters or interactions to study, or vary.

1.4 Design considerations

Don’t land your plane in forests, and don’t do experimental designs before you have considered its drawbacks

It is important to keep in mind that no experimental design is really perfect in that it can consider all aspects of an issue. This is not to discourage us. In a way, George Box’s (British statistician) quote that “All models are wrong, but some are useful” applies to experimental designs as well. As long as we remember that one single experimental design cannot be comprehensive and all-encompassing and that it is ok to be specific and clear about limitations. A perfect design doesn’t exist because we cannot possibly control for the many factors and behaviours that may affect a situation.

Therefore, since all models are wrong to some extent, researchers should check the scope of applicability and limitations of their method/model. We should choose the designs that best answer the research question, and not try to tailor the research question to the method at hand.

For instance, we may decide to base our tests on a set of observations derived from survey findings and not be aware that survey data can fail in several aspects: (1) people act differently when they realize they are under study. If asked about questions on sensitive topics (e.g., homosexuality, immigration, abortion, or Donald Trump), people understand there is a “standard” answer and so, they may hide their true feelings and give socially acceptable answers. (2) having a representative sample is difficult and expensive. In social sciences, one of the basis of experiments is recognizing regional diversity (e.g. British Columbia is different from Ontario and Ontario is different from Quebec). This can affect the interpretation of our findings and their generalizability. (3) determining the causal relations between two events is usually the goal of experimentation. However, direction of causal inference in social situations can be problematic. Traditional quantitative methods are particularly ill-designed for causal questions when the answer can go in either directions. A solution here is a carefully designed experiment with control groups, more on this later.

Nevertheless, experiments can produce many types of evidence that can be used in program and policy designs. With sufficient sample sizes, for example, randomised control trials can provide useful evidence through pre- and post-experiment analysis.

For example, a behavioural insights group examined the effect of nudges on health and wellbeing and demonstrated a massive effect default choices have on organ donation compliance rates. Those countries where people are required to opt-out of organ donation report significantly higher consent than those with an opt-in policy (Johnson & Goldstein (2003), Do Defaults Save Lives?, Science, Vol. 302).

Another example is another group who examined whether manipulating the positon of food on a restaurant menu would have any effect on consumer choices. They found that items placed at the beginning or end of the menu were up to twice as popular as when the same items were placed in the centre of the menu (Dayan & Hillel (2011), Nudge to nobesity II: Menu positions influence food orders, Judgment and Decision Making).